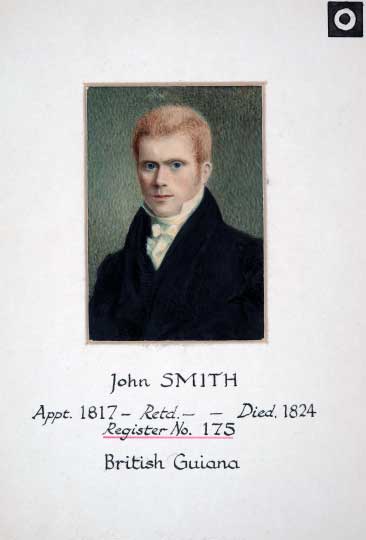

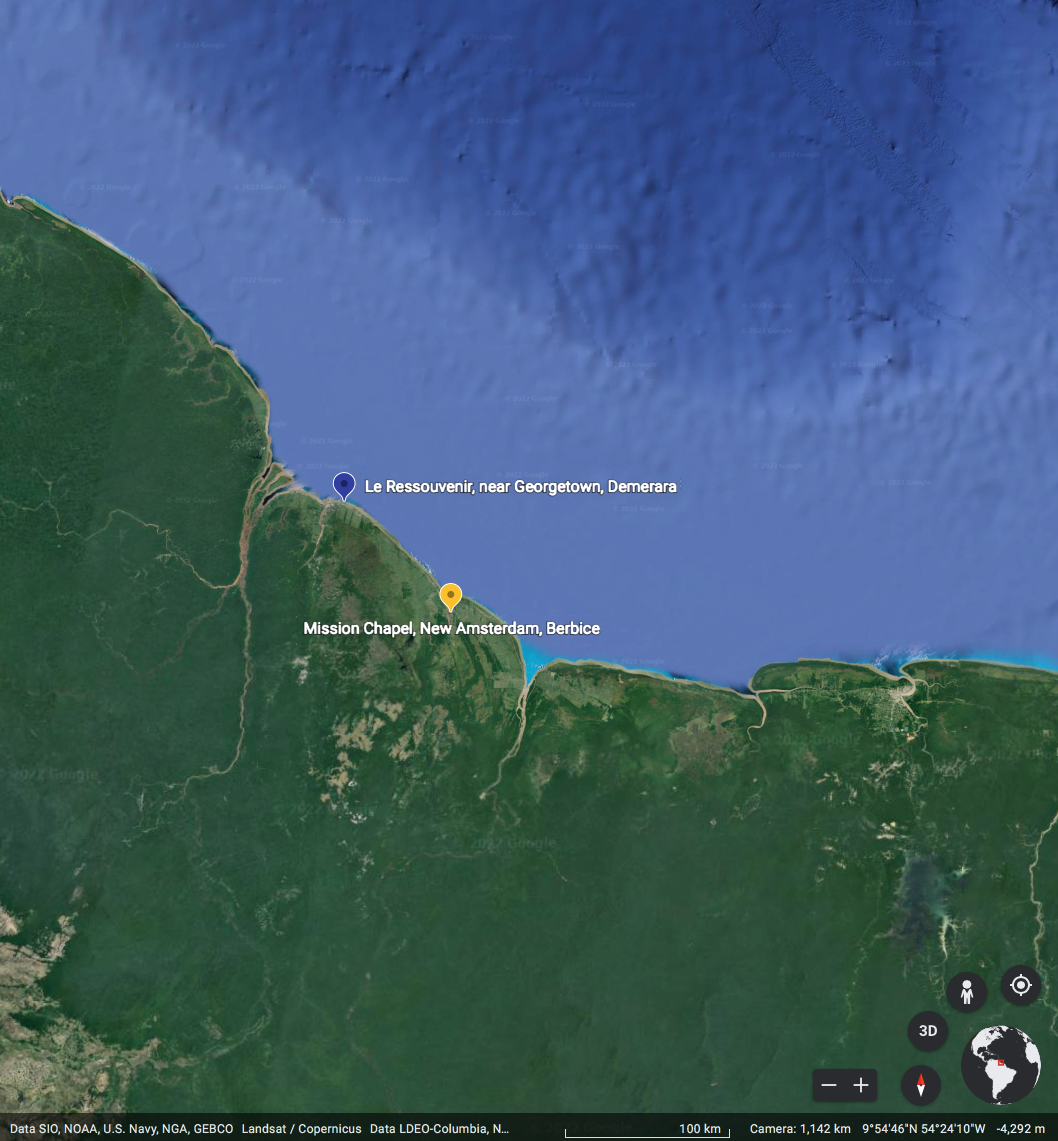

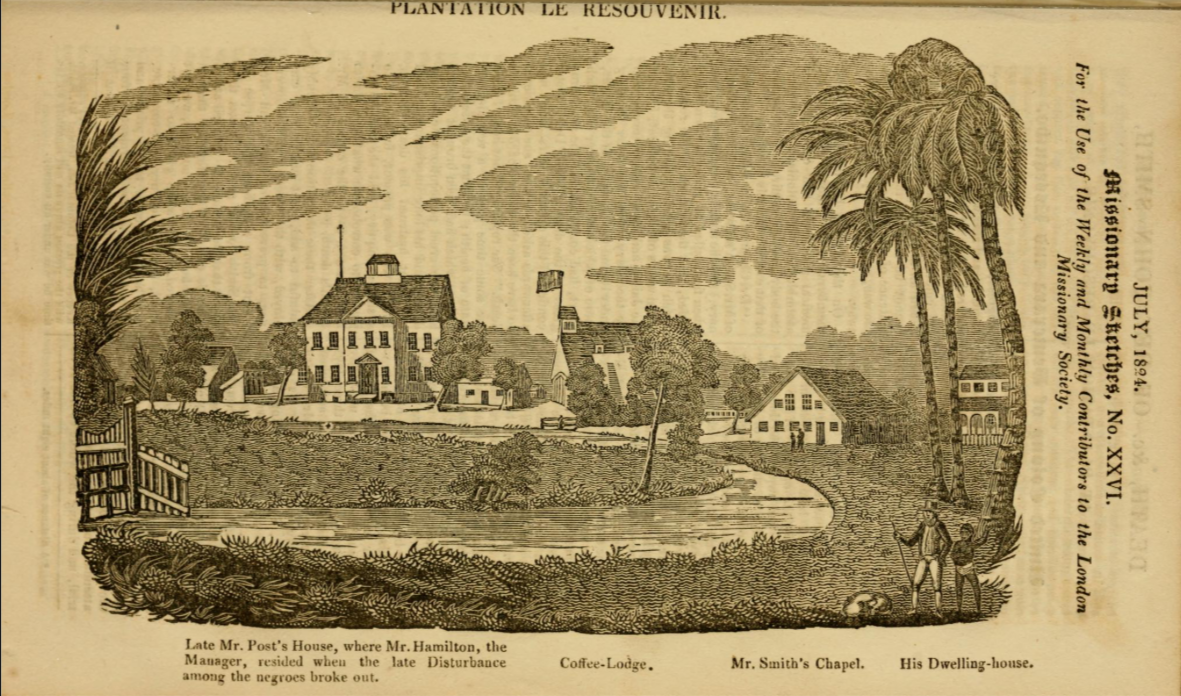

One response to the image of Pomare’s ‘family idols’ came in a letter from John Smith, a twenty-nine year old former biscuit maker who had been a missionary in Demerara for two years. He wrote from Le Resouvenir, a plantation clinging to the Atlantic coast at the edge of the Caribbean, that:

I have shown the negroes the pictures of the idols in the Missionary Sketches; and their opinion is, that they must have been made in secret; for, they say, if the people had seen the workmen make them, they could never have been so stupid as to pay them religious honours. They express the greatest compassion for those who are living in heathen darkness, and are evidently willing to do all in their power to assist in sending them the gospel.1

This short paragraph illustrates the widespread circulation of

missionary imagery, and the way that missionary periodicals

enabled an enslaved congregation of a missionary chapel to

join a global Christian community in commenting on Tahitian

religious practices.

Smith’s note suggests an attitude of incredulity that was

presumably shared by church-goers in Britain, and apart from

the hint of deliberate trickery, essentially ignores the clash

of religious practices underpinning his own missionary

engagements.

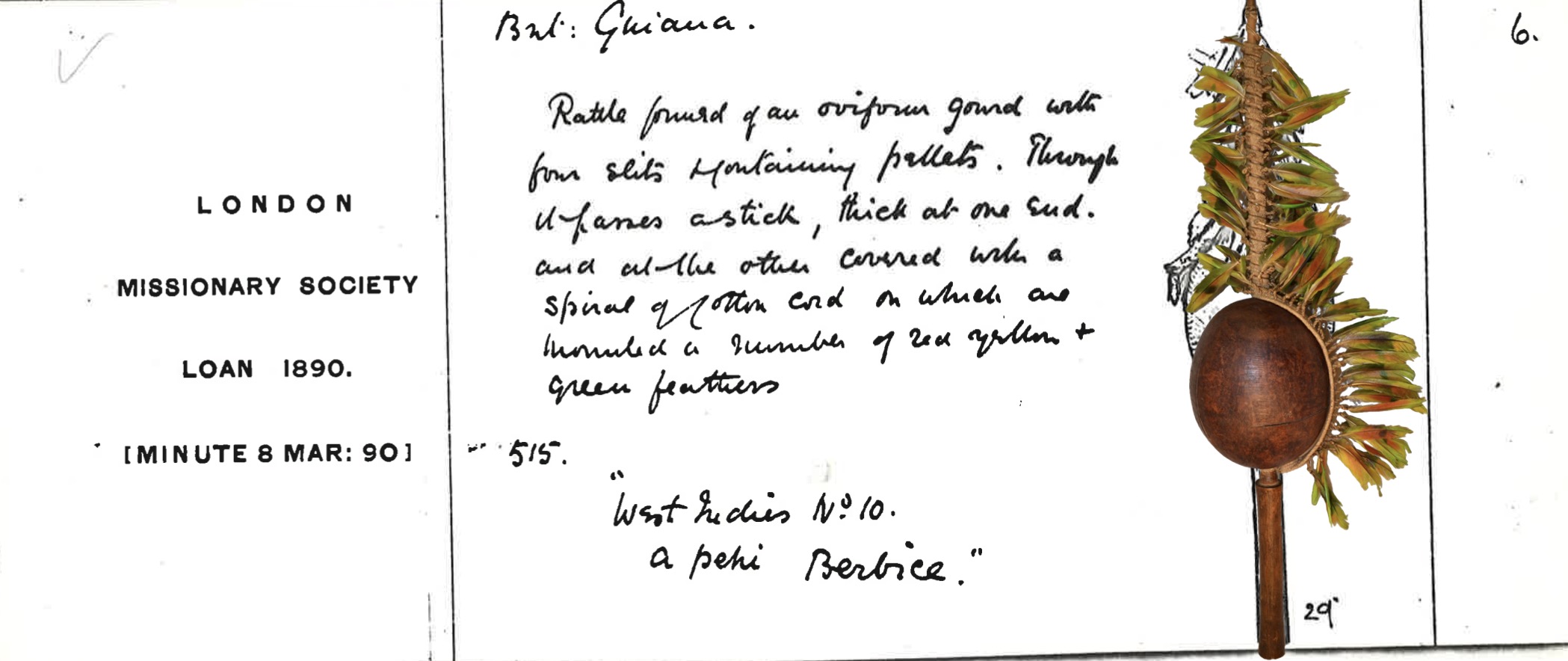

These were given material form of sorts by a magical rattle

donated to the Missionary Museum a year earlier by John Wray,

Smith’s predecessor missionary at Le Resouvenir. According to

a catalogue of the Missionary Museum, printed in London in

1826, this was:

An instrument of incantation used by the Pehemen, either to drive away sickness or to inflict it. The natives tremble at the rattle as though the earth was opening to swallow them up, and would not dare to shake it except on special occasions. They will rattle it a whole night over a person who is ill, and at the same time sing their wild songs.

Presented by the Rev. John Wray, Missionary, Berbice, 16 Feb. 1818

Like the Cape, both Demerara and Berbice began as Dutch commercial colonies. British control was consolidated during the Napoleonic wars, so the British parliament’s 1807 Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade prohibited the further importation of enslaved people from Africa.

The rising political power of evangelicals in Britain

threatened the established economic model of plantation

slavery, but also led to an increasing presence of

evangelicals on the ground in the Caribbean. John Wray used to

tell his children that as he sailed into Demerara in February

1808, the last vessel to import a cargo of enslaved people

sailed out.

This passing of ships, whether in the night or not, retains

its potential to symbolise an important shift in the tides of

Atlantic history.2

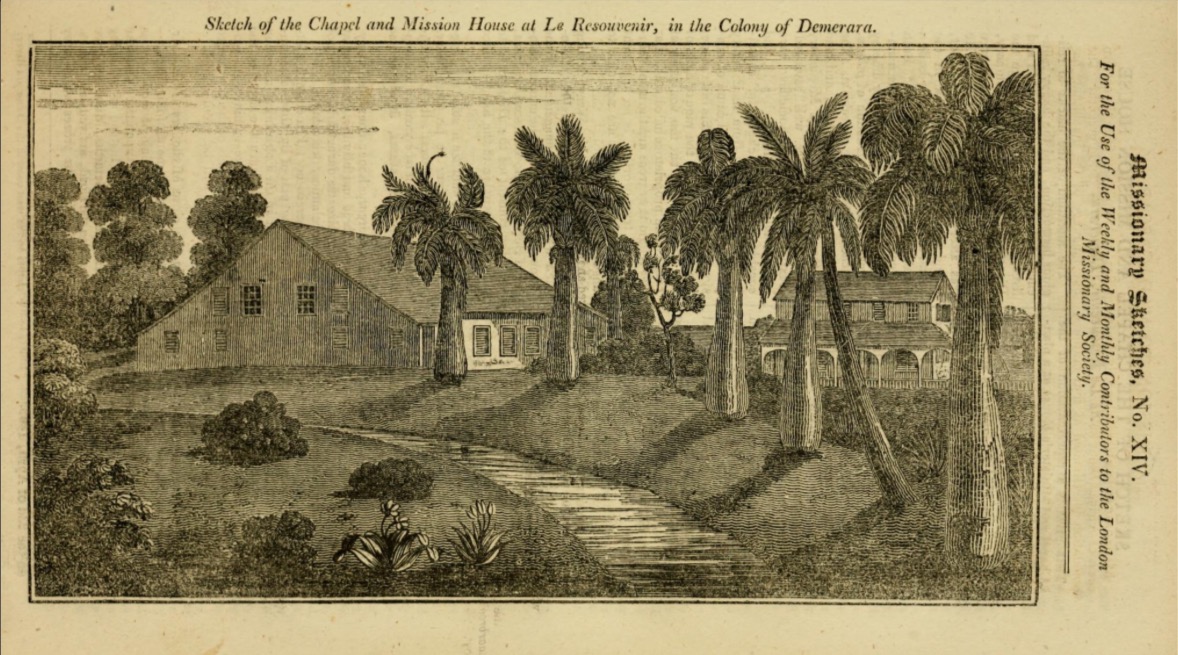

The Directors of the Missionary Society despatched Wray, aged

27, to Demerara at the end of 1807 in response to a request

from Hermanus Hilbertus Post, the Dutch-born owner of Le

Resouvenir. Post had begun his career in the Caribbean in 1774

as an overseer, but soon acquired land on which he established

his plantation.

Wracked by a sense of his own sinfulness and in pursuit of

redemption, Post built a chapel at Le Resouvenir capable of

accommodating 600 people. This was given the name Bethel, a

house of God in the ‘barren wilderness’ of slave-owning

Demerara.3

Wray’s arrival generated anxiety among the colony’s planters,

who feared he would turn Demerara into a second St Domingue –

Haiti having established its independence from France in 1804,

a mere four years earlier, following its 1791 revolution.

The planters accused Post of introducing ‘anarchy, disorder and discontent among the enslaved’.4 In 1808, The Demerara and Essequebo Royal Gazette suggested:

It is dangerous to make slaves Christians, without giving them their liberty… What will be the consequence when to that class of men is given the title of beloved brethren, as is actually done? Will not the negro conceive that by baptism, being made a Christian, he is as credible as his Christian white brethren?5

In a colony of approximately 2,500 White people, 2,500 free Black people and 70,000 enslaved Black people, around half African-born, the logic of race asserted itself in the face of claims to Christian brotherhood. Just as in South Africa, efforts were made by those with power to prevent missionaries teaching the enslaved to read and write, lest they be exposed to dangerous political texts from abroad.

When Wray began his work at Post’s plantation, he seems to

have worried mostly about the limited time available for

enslaved people to pursue religious interests. Sundays were

used to cultivate gardens for food as well as to sell produce

at market, so religious meetings were arranged in the evening,

when they had to compete with the ‘drumming, dancing,

intoxication and other evils’.6

Exposure to Christian teaching was intended to reform these

activities – drumming and dancing in particular appearing to

suggest the ongoing influence of African religious practices.

As early as November 1808, Wray was reporting that after a

funeral, some of his congregation had assembled to sing hymns

and pray rather than ‘meeting together to drum and dance, as

formerly’.7

A letter to London from Hermanus Post in January 1809

suggested that enslaved people on a neighbouring estate were:

…formerly a nuisance to the neighbourhood, on account of their drumming, dancing, &c. Two or three nights in the week, and were looked on with a jealous eye, on account of their dangerous communications; but they are now become the most zealous attenders of public worship… No drums are used in this neighbourhood, except where the owners have prohibited the attendance of their slaves. Drunkards and fighters are changed into sober and peaceable people, and endeavour to please those who are set over them.8

Wray reported that even the plantation manager was astonished by the change in his charges, who ‘Before they heard the Gospel, they were indolent, noisy and rebellious; but now they are industrious, quiet and obedient,’ but also that now people would work without the application of the whip.9

This was the argument abolitionists most wanted to make – that improving conditions for enslaved people would result in less brutality by overseers and more harmonious relations. At least from the perspective of Post and Wray, religious conversion formed a central plank in this project.

While the unenlightened attitudes of slave-owners was

something to be overcome, non-Christian religious practices

with roots in Africa among the enslaved posed an equal threat

to this new dispensation.

In May 1811, Governor Bentinck of Demerara followed Jamaica in

banning assemblies of slaves between sunset and sunrise,

effectively prohibiting Wray’s church meetings. When his

appeals to the Governor were ignored, Wray left on a cotton

ship for Liverpool. Through evangelical circles in London, he

took his complaints to the heart of government.

Returning at the end of the year, Wray had secured an official instruction to allow religious meetings on Sundays between five in the morning and nine at night, and between seven and nine in the evening on other days. When Governor Bentinck attempted to delay the implementation of this policy, he was recalled.

Wray, however, had drawn attention to himself in London, where a major experiment was in the offing. Abolitionists had argued that preventing the importation of further slaves would force plantation owners to improve living conditions so that enslaved people lived longer, were more productive and had more children.

In taking control of Berbice, the British Government had become responsible for 1100 ‘Crown slaves’ and in April 1811, a Commission for Managing Crown Property in South America was appointed. This consisted of prominent humanitarians and abolitionists such as William Wilberforce and James Stephen, who appointed Zachary Macauley, former governor of Sierra Leone, as their secretary.

Macauley wrote to Wray asking him to establish a mission to

‘Crown slaves’ in Berbice funded by the British Government, in

order to advance their ‘intellectual and moral character’.10

Interpreting this as a divine calling, Wray took on the

charge. He preached a final sermon at Le Resouvenir in June

1813 and took his family up the coast to New Amsterdam in

Berbice, still a largely Dutch-speaking colony.

‘Crown slaves’ were to be protected from the whip, provided

with task-based allocations of work and not given tasks that

could be undertaken by animals or machines. They were also to

be allowed a day a fortnight to cultivate their gardens,

freeing time for church on Sundays.

It must have been with a degree of hopefulness that Wray

joined this experiment, although he was ultimately to clash

with the Commission’s agents in Berbice – its managers

regularly provoked Wray, impregnating his servants and

withholding his pay – as well as successive Governors

(Bentinck was appointed to Berbice in 1814, following his

removal from Demerara).11

It was in Berbice that Wray became increasingly concerned with the specifics of religious practices among the enslaved.12 In an interview during 1813, Joe, accused of Obeah at the Crown plantation of Dageraad, told Wray that he was not an Obeah man, but did have supernatural powers to counteract Obeah by rites and incantations which he learned from ‘good spirits’.13

When Wray asked to meet these spirits, Joe told him his images and instruments, made from feathers and hair, had been confiscated and damaged by the Crown Agent. The distinction between malevolent action against others and healing or preventive practice seems to have been important to enslaved people, but was essentially ignored by Europeans. While Wray dismissed much of what he was told, he concluded that ‘It is impossible to describe the influence these men obtain over the minds of the negroes’.14

Diana Paton has suggested that the term ‘Obeah’, first defined as a crime in Jamaica following Tacky’s rebellion in 1760, spread around the English-speaking Caribbean at this period – ‘Obeah’ laws were passed in Berbice in 1801 and 1810.15

Tacky’s rebels had conducted oaths and rituals based on Akan practices from the Gold Coast, now Ghana, so the Act to Remedy Evils arising form the Irregular Assemblies of Slaves included a clause outlawing ‘the wicked Art of Negroes going under the appellation of Obeah Men and Women, pretending to have Communication with the Devil and other evil spirits’.16

If Obeah as a crime was originally associated with rebellion

and unrest, by implication the introduction of Christianity

should have been associated with peaceable relations between

the enslaved and their masters.

This association was quickly challenged.

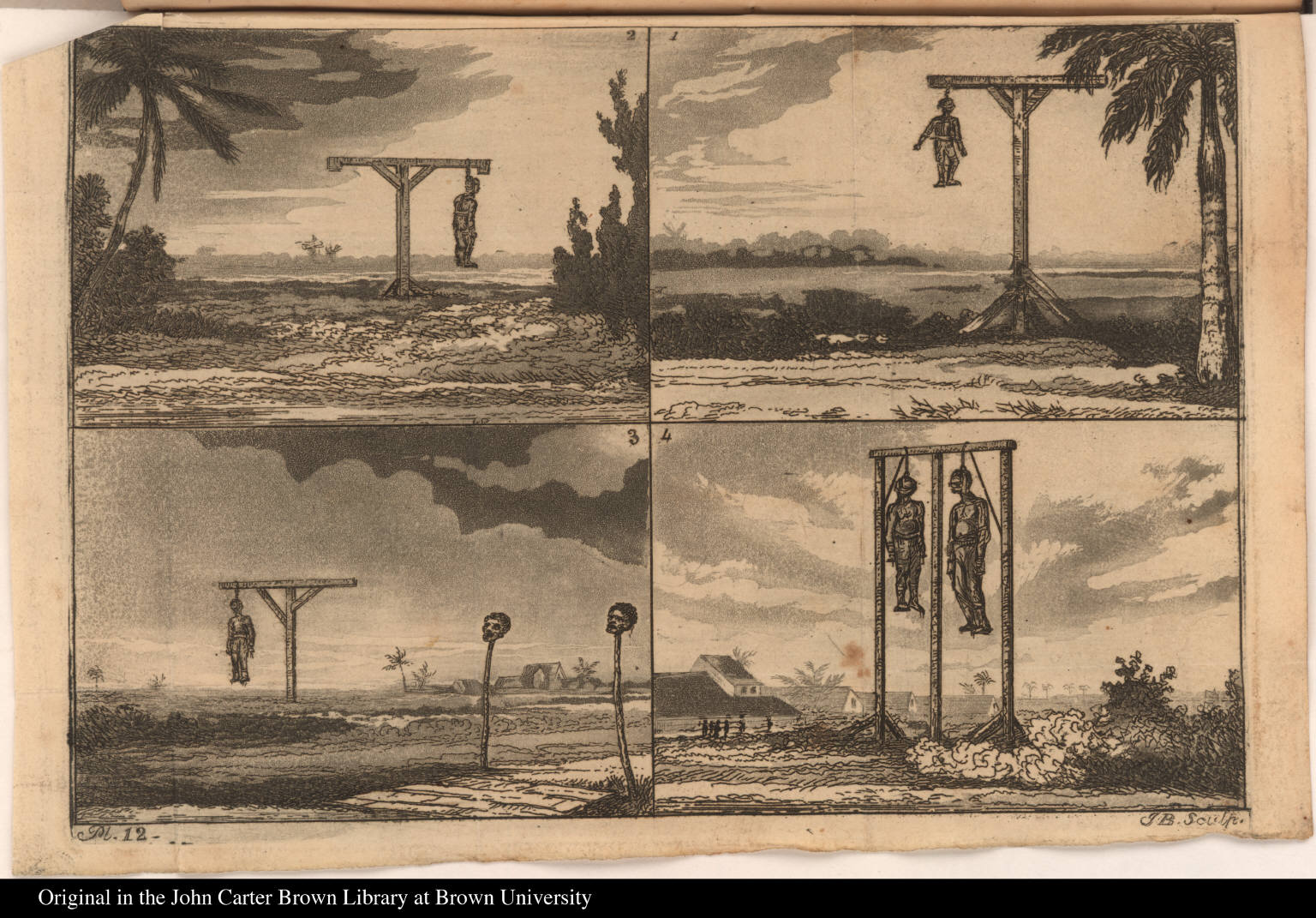

In 1814 rumours circulated across Berbice of an insurrection on the west coast, for which Wray was initially blamed by planters. It turned out, however, that none of those involved were ‘Crown slaves’, and an enquiry suggested that rather than rebelling they had been attempting to establish a society on the model of the Freemasons.

Alternative forms of authority were nevertheless viewed with suspicion, and six of those identified as ringleaders were executed, decapitated and their heads put on stakes at their home plantations. In addition, dancing was outlawed across the colony for the rest of the year, with travel between estates made conditional on the presentation of travel passes.17

Following the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 and the establishment of peace in Europe, the Crown estates and the majority of ‘Crown slaves’ were returned to the Society of Berbice in July 1816.

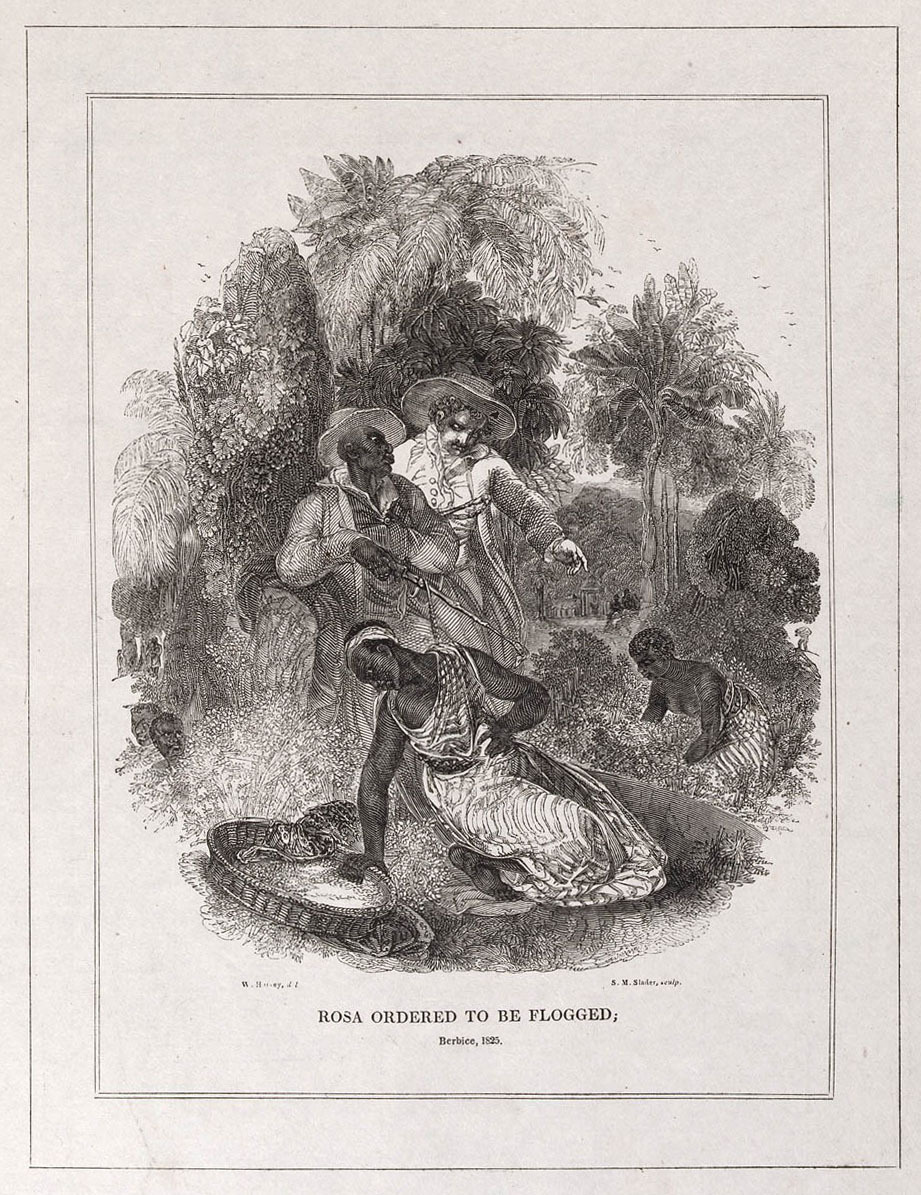

Wray remained in the colony, but his focus shifted to 300 or so enslaved artisans retained by the Crown, as well as the free residents of New Amsterdam. He continued to visit congregations at the former Crown estates, just as he made regular visits back to Le Resouvenir. It was presumably on one of these visits that Wray came to hear of the mistreatment of America, a woman from the Sandvoort estate.18

Hearing that her daughter had been flogged, she confronted the mistress of the White estate manager who had taken her daughter as a servant. For this ‘impertinence’, America, in the late stages of pregnancy was stripped naked, tied to the ground and given 170 lashes with a cart whip while the estate manager watched, smoking his pipe.

Although she survived, she lost her child, but the case deeply

distressed Wray and his wife – their daughter reported that

‘the lashes inflicted on these poor creatures seemed to eat

into his very soul’.19

This distress was undoubtedly exacerbated by the fact that

Wray’s wife had until recently been providing midwifery

services to pregnant women on the estate.

In search of justice, Wray once again sailed to Liverpool,

arriving in early 1818. While in England, he addressed a

number of Church meetings, pleading against the flogging of

women, but also presumably about the evils of Obeah. It was

during this visit that he presented the rattle to the

Missionary Museum.

In January 1819, after Wray had returned to Berbice, the Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle published a short report on the adoption of legal measures against Obeah in Martinique, noting:

In the Missionary Museum is one of the rattles, formed of a hollowed fruit, with a long handle, employed by the Obeah men in their malicious and cruel practices. We wish well to the plans of the magistracy, but are persuaded that the influence of the Gospel will prove the most effectual means of suppressing this evil.20

While the description in the 1823 museum catalogue suggested the rattle was used ‘to drive away sickness or to inflict it’, the Evangelical magazine didn’t hesitate to emphasise that it was used in ‘malicious and cruel practices’. The description of its form, however, having been made from a hollowed fruit, or more likely gourd, provides an important clue to its origin and function.

While Wray’s interview with Joe mentions images and

instruments made from feathers and hair, it does not refer to

rattles. Shaman’s rattles, frequently made from hollowed

gourds, are, however, a feature of the ceremonial practices of

the indigenous peoples of the region, with whom Wray had also

been in contact.

As early as December 1811, Wray wrote to London about a visit

to Georgetown, the capital of Demerara, by an indigenous

group, expressing an ambition to establish a mission among

them.21

In July 1816, Wray travelled up the Berbice river to visit

indigenous settlements. Here, he met an old man who told them

he was a Christian, having been baptised many years previously

by Moravians on the Courantyne River, the boundary of Berbice

with the Dutch colony of Suriname.

In December of the same year, Wray travelled forty miles up

the Courantyne River to Equevi creek, where he visited two

Warrao villages with William Ross, ‘Protector of the Berbice

Indians‘.22

It seems very likely that the rattle was collected on one of these visits – from an indigenous shaman rather than an enslaved ‘Obeah man’.

It is perhaps significant that apart from a ‘Boa Constrictor in the act of devouring an antelope’, presumably a product of taxidermy, the only other items associated with Wray in the 1826 catalogue of the Missionary Museum were an unspecified number of:

WAR CLUBS curiously carved by South American Indians.

A later version of the catalogue describes three

‘quadrangular’ clubs of hard wood, ‘used by Macusi and

Caribbee Indians of Guiana’.

The catalogue description of the rattle, given above, refers

to ‘the natives’ rather than enslaved people, many of whom in

1826 would not have been native, in that they would have been

born in Africa.

It seems very likely, therefore, that Wray’s description of

the rattle as used by ‘the natives’ for healing was amended by

someone in London who had never been to the Caribbean to add

‘an Instrument of Obeah, or Incantation, very dreadful to the

Negroes’.

Alternatively, it could indicate the regard that enslaved

people had for the ceremonial practices of the indigenous

people of the land.

The British Museum has a rattle, acquired from the London Missionary Society, that is recorded as coming from the Berbice River in Guyana by its online catalogue. It is described as: ‘Pelu, rattle made of gourd, cotton, feathers’. The photograph online appears to match the sketch on a loan slip, produced in 189 when the British Museum borrowed a selection of rare items to display from the missionary museum (LMS 6).23

Below a curator’s description, further text is recorded in quotation marks, presumably from a label or written directly on the rattle itself:

515

West Indies No. 10

A pehi Berbice.

The number 515 relates to a catalogue produced for a large missionary exhibition in Paris in 1867, the catalogue of which describes 515 as:

Un Péhi secoué sur les malades pour leur guérison.

PEHI, an instrument of Obiah, or incantations, used by the Pehemen, either to drive away sickness, or to inflict it. The natives would not dare to shake it, except on special occasions. They would rattle it all night over a person who was ill, and at the same time sing their wild song. Presented by the Rev. John Wray, Missionary, Berbice, 1818

While the description as ‘very dreadful to the negroes’ was

apparently removed from the text of the later museum

catalogue, it nevertheless still referred to the rattle as ‘an

instrument of Obiah’. This may suggest that from a missionary

perspective there was a degree of equivalence between the

healing practices of the enslaved people of African descent,

and the indigenous people of Guyana.

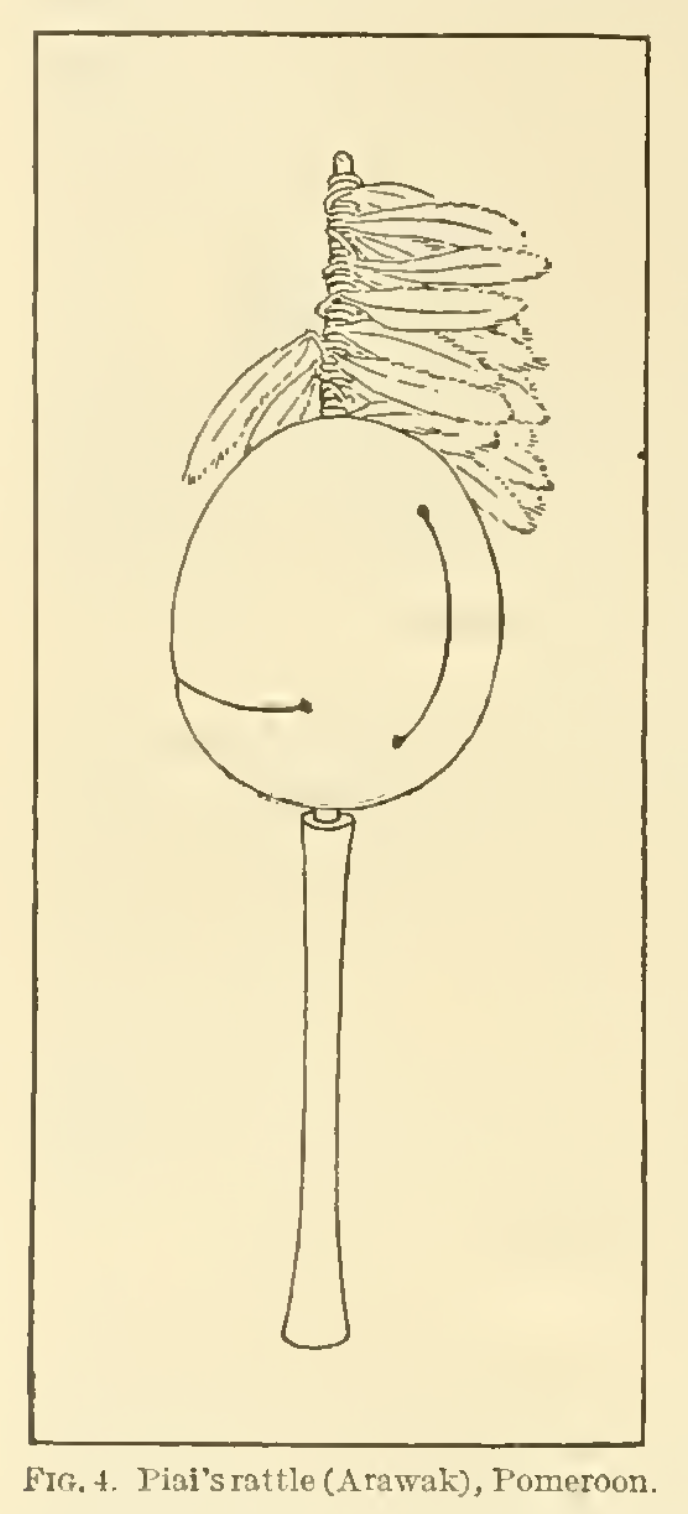

In 1913, the colonial administrator and keen amateur

anthropologist Walter E Roth, then commissioner of the

Pomeroon District in British Guiana, published

An Enquiry into the Animism and Folk-lore of the Guiana

Indians. On page 330 he included a line drawing of a rattle, very

similar in form to that in the British Museum, which he

captioned Piai’s rattle.

According to Roth, hollowed gourds were filled with seeds and stones with unusual origins which gave the rattle its power – these included seeds extracted from the Piai teacher’s stomach and stones that were a gift of the Water Spirits.

Roth was told by an Arawak ‘medicine-man’ that the feathers must come from a special kind of parrot (Psittacus aestivus) and must be plucked from the bird while it is still alive. The plumage of this species certainly seems to match the feathers on the rattle in the British Museum, even though it is now over 200 years old.24

According to Roth, the rattle itself is called, not a Pehi, but a maráka, an Arawak word that has become common in European languages, but was according to Arawak tradition a gift from the Spirits.

According to Roth, it was ‘held in great veneration even by Christian converts who have ceased to use it’ while people may ‘fear to touch it or even approach a place where it is kept’.25

In the context of missionary activity and conversion, what could be a more powerful tangible demonstration of conversion than to hand one of these potent rattles to a missionary? In addition to being a gift that demonstrated an intention to renounce spiritual practices, giving a rattle to someone like Wray removed it from a location where it posed a risk and could continue to cause harm.

In the 1960s, the anthropologist Peter Riviere similarly agreed to take a converted Trio’s shaman’s rattle away with him, ultimately donating it to the Pitt Rivers Museum. It seems that for a shaman, sending away a rattle that linked you with your spirit familiars, with which you had a close and intimate relationship, was easier than destroying it – one Trio shaman stated ‘they are like children to me… Who in the world destroys something that is like a child to him?’.26

When I contacted Peter Riviere to ask whether he could help me to make sense of the rattle and Wray’s description, he told me that he thought Pehi was a transliteration of piai, a word widely used to mean shaman or healer. The Oxford English Dictionary records the word being used in English from 1613 onwards to refer to people who were glossed as priests, doctors, diviners, charmers, sorcerers or soothsayers. This suggests that no satisfactory English equivalent was available. Riviere thought that Peheman was almost certainly a transliteration of piaiman or piaime, meaning the practice of ‘being shamanic’ – a quality that in indigenous thought everyone has, but only some develop to a high degree of mastery.27

The rattle then, was not unlike the ‘Idol Gods’ sent from Tahiti by Pomare as a token of conversion, and actually seems to have arrived at the Missionary Museum in London before the long-delayed parcel from the Pacific. It has not retained the same notoriety, illustrated by the fact that its association with Wray and the early mission to Guyana was forgotten at the British Museum.

What has been most widely remembered about Wray and Smith’s early mission in Guyana occurred in the years after the rattle’s arrival in London.

In July 1822, Wray visited his former congregation at Le Resouvenir in Demerara, which had been under John Smith’s ministry since 1817. He was pleased with what seemed to be a functioning Christian congregation and the 2000 people under instruction for Catechism, although he lamented that the missionaries were still not allowed to teach their charges to read.

In January 1823 the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the British Domininions was founded in London, as leadership of the anti-slavery movement was passed from William Wilberforce, who had effected parliamentary abolition of the trade in 1807, to Thomas Fowell Buxton. Their first achievement was the passing of a parliamentary resolution recommending further reforms.

As a result, regulations were sent to Crown colonies limiting labour for the enslaved to nine hours a day, and abolishing the flogging of women. While the Governor of Berbice asked Wray to announce these policies from his pulpit, in Demerara Governor Murray attempted to delay the implementation of these measures. Rumours spread, and some believed he was suppressing a full grant of freedom.

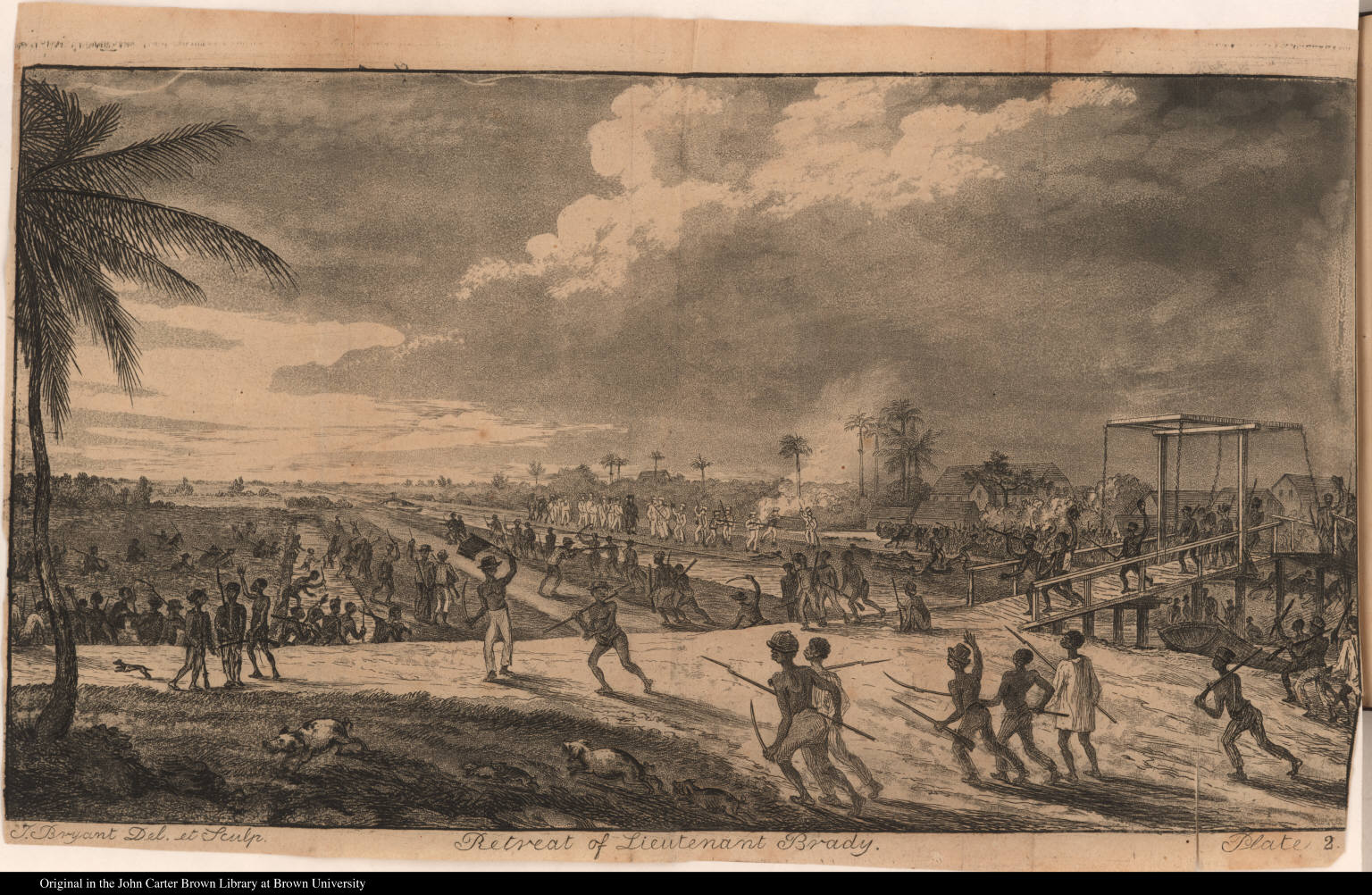

After six weeks with no announcement, a meeting was held on

one of the estates that neighboured Le Resouvenir after the

church services on Sunday 17 August 1823. The following day

some of the enslaved congregation came out on strike.

When the Governor rode out to meet a group of forty men who

had gathered, finally telling them the details of the new

regulations, they refused to lay down their weapons and shots

were fired.

The subsequent uprising seems to have been initiated by Jack

Gladstone, son of Quamina (or Kwamina/Kwami) a carpenter and

stalwart member and deacon of John Smith’s congregation at Le

Resouvenir. Jack took his surname from the owner of his

estate, Sir John Gladstone, whose own son William would the

become Prime Minister of Britain 45 years later.

While Quamina seems to have attempted to prevent an outbreak

of extreme violence, locking estate overseers and managers in

the stocks rather than killing them, the Governor and planter

society marshalled troops to send out against the rising.

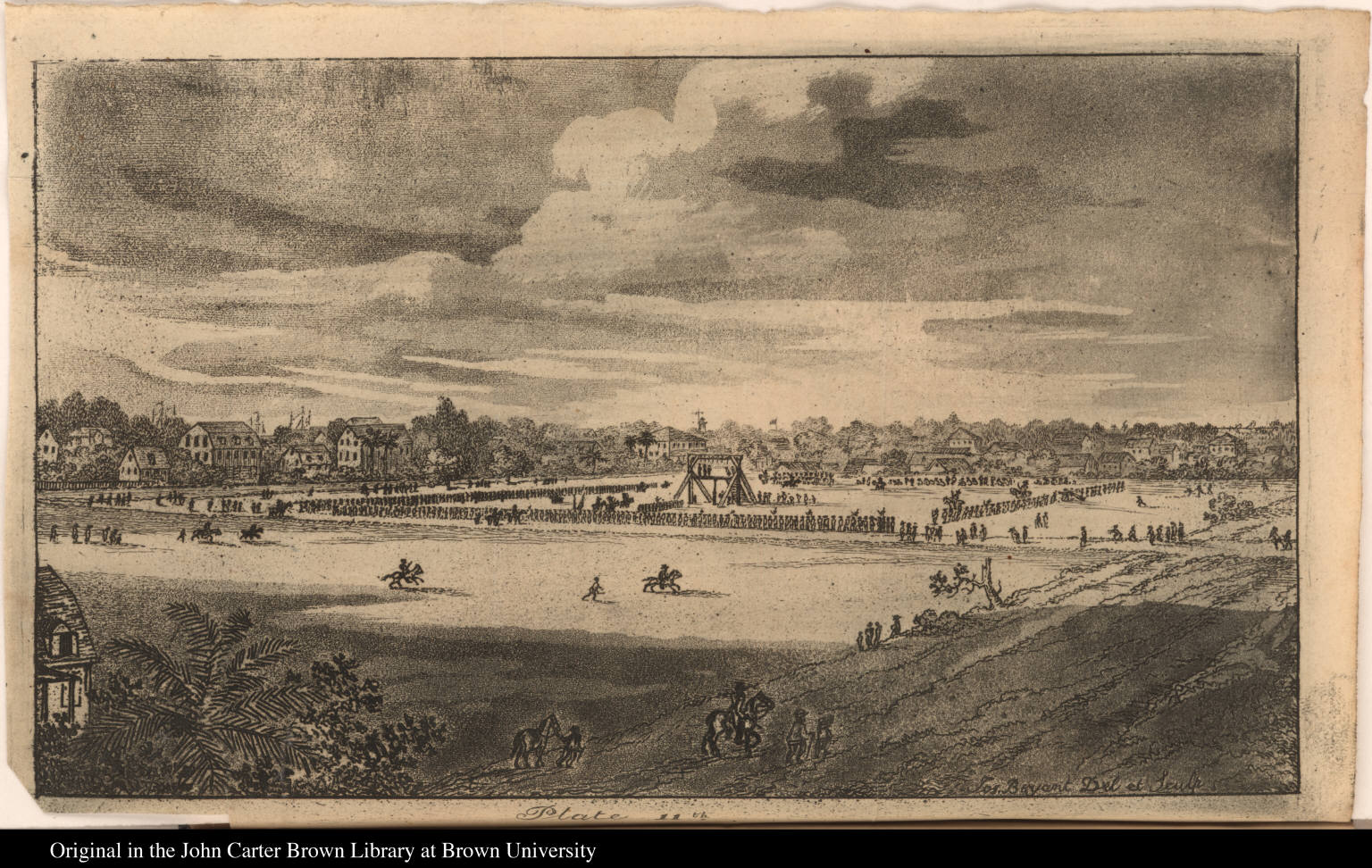

200 people were killed in the action and martial law was

imposed, with a further 50 people put to death and many others

whipped.

Quamina seems to have been blamed for the uprising and was shot while fleeing, his prayer book and hymn book still in his pocket. Instead of receiving a church burial, his body was hung from a gibbet at the entrance to the estate on which he had lived. Jack Gladstone was captured, sold and deported to St Lucia.

Amidst the uprising, rumours spread among planters that missionaries had prior knowledge of its organisation because of their close connections with a number of the ringleaders. John Smith was arrested and held for seven weeks, before being tried by Court Martial on 13 October 1823 for four charges that included:

- Promoting ’discontent and dissatisfaction in the minds of the Negro Slaves towards their Lawful Masters, Managers and Overseers’ and exciting Revolt

- Advising, consulting and corresponding with Quamina both before and during the revolt

- Not making the intended rebellion known to the proper authorities

- Not using his best endeavours to suppress, detain and restrain Quamina once the rebellion was under way.28

Found guilty of all four charges, Smith was sentenced to death by hanging, but the court recommended mercy ‘under the circumstances of the case’. The final decision was referred to London, at which point Smith was taken to an ordinary gaol where he was held for another seven weeks.

Already unwell, Smith died on 6 February 1824, before the news reached Demerara that his life was to be spared (but banished from all British Caribbean colonies). Authorities arranged for his burial to be carried out secretly in the middle of the night and demolished the grave his supporters built.

As a result of Smith’s death, the London Missionary Society gained its first martyr – in the years that followed he became widely known as the ‘Demerara Martyr’. Outrage in Britain at Smith’s death – together with the widespread loss of life among the enslaved – played a significant role in mobilising public support for the campaign to abolish slavery, culminating in the 1833 Act for the abolition of slavery throughout the British Colonies.

In 2018, the President of Guyana, David Granger declared that 20 August would henceforth be known as ‘Demerara Martyrs’ Day’, extending the category of martyrdom to all those who participated and were killed in the uprising. He committed to building a new memorial at Independence Park in the capital, the former parade ground where the executions of those condemned to death by Court Martial were carried out.

Notes

-

Smith, Thomas. 1825. The history and origin of the missionary societies. Vol. II. London: Thomas Kelly & Richard Evans, p.334. ↩︎

-

Smith, Thomas. 1825. The history and origin of the missionary societies. Vol. II. London: Thomas Kelly & Richard Evans, p.334. ↩︎

-

Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1808, p.443 ↩︎

-

Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle, January 1811, Memoir of the Late Hermans Hilbertuns Post by John Wray, p. 7 ↩︎

-

Rain, Thomas. 1892. The Life and Labours of John Wray, Pioneer Missionary in British Guiana. London: John Snow, p.37. ↩︎

-

Richard Lovett. 1899. The History of the London Missionary Society 1795-1895, volume 2, p. 320. ↩︎

-

Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1809, p.126 ↩︎

-

Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle, January 1811, Memoir of the Late Hermans Hilbertuns Post by John Wray, p.41. ↩︎

-

Missionary Transactions Volume 3, p.226: https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/GrAPAAAAIAAJ?gbpv=1 ↩︎

-

Thompson, Alvin O. 2002. Unprofitable Servants: Crown Slaves in Berbice, Guyana, 1803-1831: University of West Indies Press,

p.70. ↩︎ -

Thompson, Alvin O. 2002. Unprofitable Servants: Crown Slaves in Berbice, Guyana, 1803-1831: University of West Indies Press. ↩︎

-

Costa, Emilia Viotta da. 1997. Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood: The Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.107. ↩︎

-

Rain, Thomas. 1892. The Life and Labours of John Wray, Pioneer Missionary in British Guiana. London: John Snow, p. 113. ↩︎

-

Rain, Thomas. 1892. The Life and Labours of John Wray, Pioneer Missionary in British Guiana. London: John Snow, p.144. ↩︎

-

Paton, Diana. 2015. The Cultural Politics of Obeah: Religion, Colonialism and Modernity in the Caribbean World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

-

Rain, Thomas. 1892. The Life and Labours of John Wray, Pioneer Missionary in British Guiana. London: John Snow, p. 122. ↩︎

-

Rain, Thomas. 1892. The Life and Labours of John Wray, Pioneer Missionary in British Guiana. London: John Snow, p. 152. ↩︎

-

Rain, Thomas. 1892. The Life and Labours of John Wray, Pioneer Missionary in British Guiana. London: John Snow, p. 152. ↩︎

-

Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle, January 1819, p. 28 ↩︎

-

Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle, 1811, 153-154 ↩︎

-

Rain, Thomas. 1892. The Life and Labours of John Wray, Pioneer Missionary in British Guiana. London: John Snow, p. 148. ↩︎

-

Many thanks to Jim Hamill for providing me with a digitised version of this. ↩︎

-

Roth, Walter E. 1915. An Inquiry into the Animim and Folk-lore of the Guiana Indians. Thirtieth annual report of the Bureau

of American Ethnology, 1908-1909, 103–386. Bureau of American Ethnology, p. 330. ↩︎ -

Roth, Walter E. 1915. An Inquiry into the Animim and Folk-lore of the Guiana Indians. Thirtieth annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1908-1909, 103–386. Bureau of American Ethnology, p. 331. ↩︎

-

Grotti, Vanessa Elisa, and Marc Brightman. 2018. Narratives of the Invisible: Autobiography, Kinship and Alterity in Native Amazonia. In Animism Beyond the Soul: Ontology, Reflexivity, and the Making of Anthropological Knowledge, edited by K. Swancutt and M. Mazard. Oxford: Berghahn, p.101. ↩︎

-

Personal Communication: Email 14 February 2022. ↩︎

-

Bryant, Joshua. 1824. Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara which broke out on the 18th of August 1823. Georgetown, Demerara: A. Stevenson, pp. 91-92. ↩︎